- CLAN O'BYRNE HOME PAGE

- New Page

- NEW!! UNCOVER YOUR PAST ! !

- CLAN O'BYRNE EVENTS ARCHIVE

- Who do YOU think you are ? The Clan O'Byrne DNA Project

- FORUMs

- BYRNE HERALDRY

- Clan O'Byrne Gathering Rally Poll

- The Gathering Rally Quick Guide

- News , Updates and Archives

- Clan O'Byrne Background

- The Clans of Ireland

- Histories of the O'Byrnes

-

Sept families of the Leinster Byrnes

- Leinster Clans Alliance

-

Clan Rallies of the O'Byrnes

- St. Geri 2008

- Well known and not so well known Byrnes

- Ancestors sought and hoped for.

- Blogs for Byrnes

- Clan O'Byrne Video Vault

- Publications, Links and Sources

- Irish Order of Knighthood

- Google Wicklow

- Drives thro County Wicklow

- Membership registration form

- Clan Ó Byrne Members only

The O'Byrnes and O'Tooles

By Gerard Slevin, former Chief Herald of the Irish Genealogical Office.

|

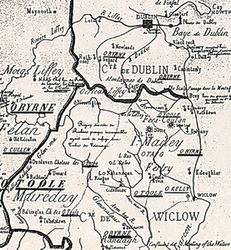

One of the many things about Dublin which make it

remarkable as a capital is the variety of the country which surounds it. A sandy beach is more or less round the corner, a little outside in one direction and you are on the flat, fertile plain of Kildare, a little outside in another direction and you are surrounded by the majestic cavalcade of the Wicklow mountains. The O'Byrnes and the O'Tooles observed a Danish city from the plain and a Norman city from the mountains, against the constant limit of the sea. That, like all summary statements, is open to qualification, but it gives us a starting-point. There was, according to the genealogies, a prince called Tuathal, son of Ughaire, King of Leinster, who died in the year 956. There was also Bran, son of Maolmordha, King of Leinster, who died in Cologne in the year 1052. From these the O'Tooles and the O'Byrnes derive their surnames. At this point a distinction is inescapable: there are O'Tooles in Ulster and O'Bymes in Connacht who are quite distinct from the Leinster families of whom we write. But these latter are more than enough for a single article. We see them first inhabiting the broad stretches of Kildare, the O'Byrnes lords of the northern half of what is now the county of that name, the O'Tooles lords of the southern half. The embattled Normans coveted these territoties and the two clans were forced to withdraw into the mountainous area to the south east. Here was a natural stronghold and almost impregnable. From this maze of hill and glen they would threaten for centuries the capital city below. Even now, if you stop on a mere shoulder of a hill - on the way up from the Pine Forest to the Featherbed Mountain, say - and look down, the city on the plain below looks unexpectedly vulnerable. It was much smaller, of course, when the O'Byrnes and the O'Tooles viewed it from the hills, but for them much more dangerous. It was a constant threat to them, but also were they a constant threat to it. Their power and its exercise were remarkable. When Bruce's march through Leinster in the fourteenth century provided an opportunity for action they swept down on the lowlands to the east and captured the important towns of Arklow, Newcastle and Bray. Much later in the same century the tenants of lands around Tallaght, a few miles from Dublin itself, were secure in their holdings as long as they paid 'black rent' to O'Toole. The personification of this centuries-long struggle is Fiach MacHugh O'Byrne. His appearances on the stage of the late sixteenth century are frequent and significant. He is noted by Edmund Spenser, that gentle master of English verse. Spenser saw the great importance of O'Byrne's inaccessible terrain and its situation within striking distance of the capital. No doubt Fiach, about whose life and deeds there hangs a certain mystique, was the product of his country and his time; who isn't? He was of a junior branch of the O'Byrnes but was accepted as chief of his people, though it seems that there were some who disputed his right. He was about twenty-five years old when he attracts attention for the first time, in connection with the escape of Sir Edmond Butler from Dublin Castle.Fiach's life, indeed, is a string stretched taut between the Castle and the mountains. In 1572 he was implicated in the killing of one Robert Browne of Mulcronan. He was confined to his own territory but he then invaded Wexford and saw his plunder safely back to the fastness of Glenmalure. In 1573 he received a pardon, but when returning from the wedding of his sister to Rory Og OMore in Laois in the same year he was attacked by the sheriff of Kildare. He defeated and captured the sheriff, held him to ransom on very severe terms for a while, but was later pleased to release him 'for a cónsideration'. The death of Fiach's brother-in-law Rory in 1578 made the authorities apprehensive as to Fiach's conduct, but in that year he submitted formally in Christ Church in Dublin. Notwithstanding the submission he was reported to be the 'most doubted man of Leinster after the death of Rory Óge. In 1580 he swept down upon Rathcoole, a village near Dublin, and burned it, and the inhabitants of the suburbs trembled again when they looked at the mountains. He made further submissions in the following years, but when Red Hugh O'Donnell and Art O'Neill escaped from the Castle in 1592 it was towards Feaghe and his snow-bound fortress they directed their feeble steps. In 1597 he was to meet a formidable adversary in Sir William Russell, and was taken by surprise by a certain sergeant of Russell's forces named Milborne. So great was the rage of the soldiers that his captor had to strike off Feaghe's head, which was placed for a time above the gate of the Castle. A story, perhaps, of old, forgotten, far-off things. But guerilla warfare is very much part of our own age. Anybody now who tries to visualise the northern princes at the snowy door of death and O'Byrne's men seeking them will not be without some understanding of the place, the time and the people. |

We must not let the O'Byrnes over-shadow the O'Tooles.

There is one at the very least of these latter whose name will never die. Laurence O'Toole was born before his people were driven from the comfortable plain, but he nonetheless knew the lonely splendour of the mountains at an early age. He was the son of Murtagh O'Toole, chief of Ui Muireadaigh, who gave the boy Laurence as hostage to Dermot macMurrough, King of Leinster. Murtagh, learning in due course that his son was being harshly treated by MacMurrough, seized twelve of the king's followers and threatened to kill them if the boy's condition was not improved. Dermot sent Laurence to Bishop of Glendalough in the heart of Wicklow. In the unique atmosphere of that valley the boy found the direction of his days. At twenty-five he was coarb of Saint Kevin, ruler of his monastery. In the year 1162 Gelasius, the Primate, appointed him Archbishop of Dublin, an office which he filled with both fervour and discretion for nearly twenty years, and he is today the patron saint of the diocese. In a self-indulgent age it is worth pausing for a moment to study this Laurence. He was an active and practical man, journeying to England to have audience of Henry II, to Rome to attend a General Council. So deeply involved was he with the affairs of his time that he appeared in arms in 1171 to assist in expelling the Norman invader. A prelate, you might say, whose thoughts were largely of this world. In fact his thoughts were constantly of another world. He never ate flesh, he wore a hair-shirt, he mixed ashes with his bread. Our view - that a certain amount of comfort and relaxation must accompany hard work - would probably never have occurred to him. Oddly enough, the second most celebrated O'Toole of the Middle Ages was also deeply involved in matters ecclesiastical, but in a way far removed from that of Laurence. Adam Duff O'Toole early in the fourteenth century adopted and professed certain unorthodox opinions. It is said that he denied the Incarnation, the doctrine of the Trinity, and the resurrection of the dead, that he held the scriptures to be fables and the Apostolic See to be guilty of falsehood. In that age there was only one penalty to be expected for such assertions and one cannot but think that Adam Duff must have known it. He was tried, found guilty of heresy and blasphemy, and in 1327 was burned alive at Le Hogges, a mound in Dublin near the present church of Saint Andrew, in the midst of the sparkling river of traffic flowing from Grafton Street to College Green. Perhaps one motorist out of the thousands will say a prayer for Adam's soul. The O'Byrne's and the O'Tooles stood side by side throughout centuries of warfare. But the Irish do not regard such a precedent as binding them to conformity. Time can bring changes and opposing points of view. A very distinguished soldier, Bryan OToole, served in the British army in two continents and many countries before he died, much honoured, in 1825. Amongst his many engagements had been a battle at Vinegar Hill in County Wexford. in 1798. On the other side of that battle was one Miles Byrne, then aged no more than eighteen. He too was to become a very distinguished soldier. He escaped imminent capture by disguising himself as a car- driver, and made his way to Dublin. In 1803 he was introduced to Robert Emmet, and in the plans for the capture of Dublin Castle Byrne was assigned the command of the Wexford and Wicklow men who were to make an assault from the Ship Street side. After the collapse of this second rising he went to France, became an officer in the Irish legion which Napoleon had formed, and served his chosen masters as well if not better than O'Toole served his. A monument in his honour stands today in the cemetery at Montmartre. Not that any O'Byme or O'Toole really needs a man-made memorial. The Dublin and Wicklow mountains are their monuments, threatening an enemy with massive shoulders or welcoming a friend into their secluded valleys. Gerard Slevin former Chief Herald, Irish Genealogical Office. First published in An Leabhar Branac in 1991. |

< Back to History

Design and Graphics by Val Byrne. Copyright © 2013 Val Byrne. All rights reserved.